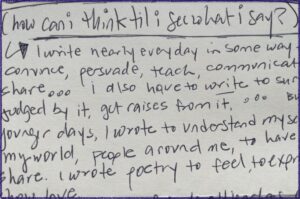

“How do I know what I think until I see what I say?” – E.M. Forster

In October of 2023, I decided to attend a writing retreat. And what a treat indeed: two days dedicated entirely to writing, with workshops and keynote speakers and food provided, in a beautiful out-of-the-way setting. I did this in the midst of So. Many. Other. Situations. that needed my attention. You know, the usual: work, family, health issues, finances. But I went anyway. I was inspired to go after I found out about the opportunity from one of my very good friends – a writer and my walking partner, who, in fact, I do believe provided the inspiration FOR this very event! (Thank you, my friend!)

I am here because I wanted to carve aside time to actually think and write, to set aside space and opportunity for the very thing that is at the heart of my work – communicating ideas – but is something that I rarely get to do any more. So why not try it out? Try to block out the emails, the texts, the planning, the arranging, … All. The. Other. Work.

And so now, here I sit, writing this.

For our first session, I chose “Prewriting.” It was amazingly crafted by the instructor, helping to pull out from the group of writers in attendance what they do to write – why they do it – and what sometimes stops them from doing it. One of the very important insights from this session was that we are always writing. Pre-writing or writing is not something that just happens when you actually put pen to paper or fingers to a keyboard. It’s the thought that hits you in the shower, on the walk. It’s the story that comes to you when you’re chopping vegetables. It’s the email or text you compose to your friend. It’s the quiet time, the loud times, the active times, the silence. It’s the routines and the surprises. It’s what you’ve read and experienced. It’s the people around you. It’s the people that haunt you. It’s the places you’ve been. Or the places you want to go.

This is all true. In fact, the idea for my next blog entry came to me on the 2.5 hour drive to this writing retreat, a drive that started on I-55 north out of St. Louis, toward Chicago, a trip I’ve taken hundreds of times in between my family’s hometown and my husband’s. Perhaps this is what led my brain to pre-write and consider the idea for my next blog focused on space and how it shapes who we are, what we think, how we communicate, and also (in tune with this current event I’m experiencing) what we ultimately write about.

This wasn’t the only insight I gained from the retreat, though. We also reflected upon how writing is deeply personal and how writing is hard. These may not seem like deep insights or something that we need to be reminded about. But in the field of education research – what I essentially do with my work time and help others learn how to do – we spend a LOT of time writing. I don’t think we acknowledge the personal and the difficulty often enough in academic writing. We’re just supposed to know how to do it and do it well by the time we get into graduate school. However, how can we sustain a career of writing if our work is not somehow personal to us? And, ultimately, who reads our own writing the most? We do! (Well, we do if we edit our work like we should! 🙂 ) We also don’t acknowledge often enough how hard it is. It is, as our instructor pointed out, a technology, something we learn, a craft we have to practice. These are additional, important insights that I will carry with me, as I continue on my own writing and life journey, and as I support others in theirs.

So, as I finish this retreat, I’m working on my next blog entry, which I hope will become a new regular series. I’m going to aim for once per month, and maybe someday that will turn into once per week. I will draw from all the pre-writing I naturally do in my daily life (thank you to my instructor, our class, and feminist scholars for pointing out the richness and ideas generated from everyday lives!); I will acknowledge and revel in the difficulty of the work; and I will do this as a gift to myself, to recognize that writing is deeply personal, even as I share it here, with you. Adelante and onward to this new writing and sharing journey!